Thousands of students descended on the modern new campus on opening day in September 1967. There were housewives and veterans, recent high school grads and draft dodgers. They were future nurses and medical assistants, technicians, musicians and tradesmen. Many were educationally disadvantaged students who otherwise had little chance of an education beyond high school.

Many had come to this location as children, for they gathered at the site where once had stood The Comet, Amerca’s tallest and longest roller coaster with nine drops, a double dip and a 500-foot tunnel. On Friday July 19, 1963, after a restaurant fire, the Comet had watched as the rest of Forest Park Highlands burned to the ground beneath it. The Comet was disassembled and the charred remains of the Highlands bulldozed. In its place rose what then was known as Forest Park Community College.

Many had come to this location as children, for they gathered at the site where once had stood The Comet, Amerca’s tallest and longest roller coaster with nine drops, a double dip and a 500-foot tunnel. On Friday July 19, 1963, after a restaurant fire, the Comet had watched as the rest of Forest Park Highlands burned to the ground beneath it. The Comet was disassembled and the charred remains of the Highlands bulldozed. In its place rose what then was known as Forest Park Community College.

Opening in 1967, college construction would continue for three more years. By 1970, William Moore could note in Against the Odds that 307 other community colleges already had sent representatives to Forest Park Community College to observe and learn. Forest Park was designed to be a leader that other colleges follow.

And the best designers lay behind plans for the new campus. From 1964 to 1967, acclaimed mid-century architect Harry Weese and his son Ben had worked with landscape architect Dan Kiley—the father of modern landscape architecture—to design an integrated, modern campus.

Fifty years later, St. Louis Community College plans to demolish two of Weese’s mid-century towers at the heart of the complex on Oakland Avenue and construct a new Allied Health building on Kiley’s lawn.

Harry Weese, Urbanist & Preservationist

A midwesterner trained at MIT and Yale, Harry Weese studied urban design at Cranbrook under Eliel Saarinen. His fellow students included Charles and Ray Eames, Harry Bertoia and Florence Knoll. He worked briefly for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in New York during the late 1940s before opening his own practice in Chicago.

Harry Weese loved old buildings, loved cities, loved public spaces, loved modern design and loved alcohol. All these he loved greatly. Before the last of these loves finally took its toll, Weese made major contributions in all of the other areas. As a juror in the competition to design the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, his was the voice that advocated against great opposition for Maya Lin’s wall of names. In his 1998 obituary, the New York Times describes Weese as “the architect […who…] produced some of the most powerful public spaces of our time.”

Weese was among the second generation of modernist architects like Eero Saarinen, I.M. Pei and Philip Johnson. Though Weese never achieved the same international fame of Saarinen or Johnson, in some way his impact was greater. A rare advocate of historic preservation among modernists, Weese was partly responsible for saving Chicago’s Navy Pier, and in 1978 he even proposed that that city’s “L” stations be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1967, he undertook the renovation of Adler and Sullivan’s Auditorium Theater in Chicago. He supervised the restoration of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and Union Station in Washington.

Weese was also unabashedly an urbanist. Weese argued that the post-war boom in suburban development was wasteful and inherently unsustainable, and he advocated for higher density middle-class housing with access to public spaces and amenities. In an article in Places Journal, Ian Baldwin argues that Weese’s “unrelenting urban boosterism and deep commitment to public life and preservation made him arguably more influential than any of his contemporaries.”1

Weese’s Kinder, Gentler (Humanistic) Brutalism

Weese brought an independent voice to his design work. At a time when modern architecture conjured images of cold and expansive concrete brutalism, Weese brought in warmer materials and local textures. His 1958 United States Embassy in Accra, Ghana included louvered mahogany bays floating above delicate white pilotis. The overall effect is organic, warm and modern.

In his 1962 First Baptist Church in Columbus, Indiana—the church is a national historic landmark—Weese made use of warm red brick in a sculptural design that makes for a kinder and gentler interpretation of the brutalism then dominant in Europe and America. When much modern architecture had become formulaic, Weese’s 1968 Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist on Chicago’s Wacker Drive provided an expressive solution to an awkward site along the Chicago River, and it did so with a massing that addressed the monumental scale of the neighborhood.

1962 First Baptist Church—Columbus, Indiana:

1968 Seventeenth Church of Christ, Scientist—Chicago:

Much of Weese’s work is in the warmer materials of stone, brick, and wood. Yet he also experimented with steel, albeit the warm corten steel beloved of so many modern sculptors. In The Architecture of Harry Weese, historian Robert Bruegmann notes designs that push far beyond the orthodox International Style of Mies van der Rohe. Weese’s 1968 Shadowcliff is a home office suspended from corten beams cantilevered out from a Wisconsin rock face high above Lake Michigan. A window in the floor allows for views in all directions.

The Graham Foundation describes the work of Weese and Associates as syncretistic.

Although Weese was a self-avowed modernist, his early work … disregards numerous modernist conventions. Unfettered by the philosophical preconceptions of Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, Weese appears, like Saarinen and Aalto, to subscribe to a more humanistic modernism. … Weese’s buildings provide insight into a uniquely American approach to mid-century modern architecture that never lost sight of the social, political, and economic realities of contemporary life.2

Weese is perhaps best known for his design for the Washington Metro. At the height of the Cold War, the Metro’s graceful concrete vaults—now threatened with white paint by government bureaucrats—were designed to contrast with the fussy ornament of Moscow’s Stalinist subway stations. Good modern design has an economy of form, and Weese’s Metro remains a monument to the subtlety of the modern vision.

The Design for the College at Forest Park

The Junior College District of St. Louis and St. Louis County planned for a college on the site of the Highlands. It was one of three colleges backed by a $47 million bond issue, which at the time made it the most ambitious building program in the history of public higher education in the United States. According to the District minutes, the 35-acre Forest Park site was intended to house 7,000 full-time day students.

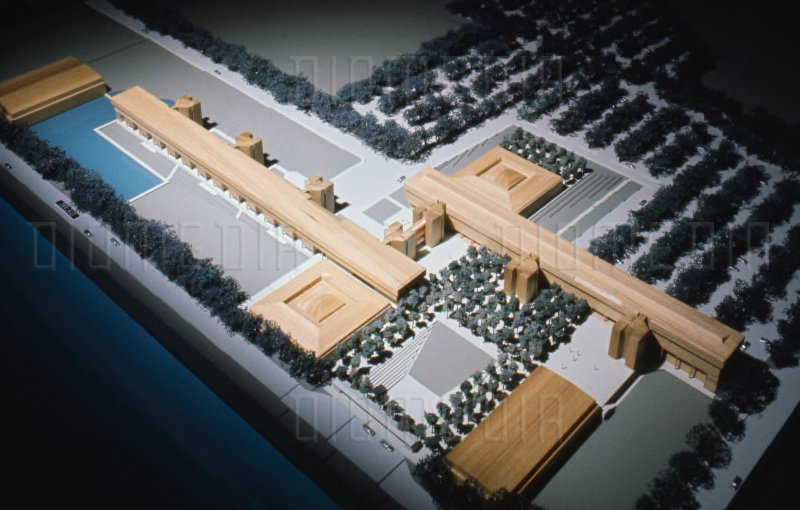

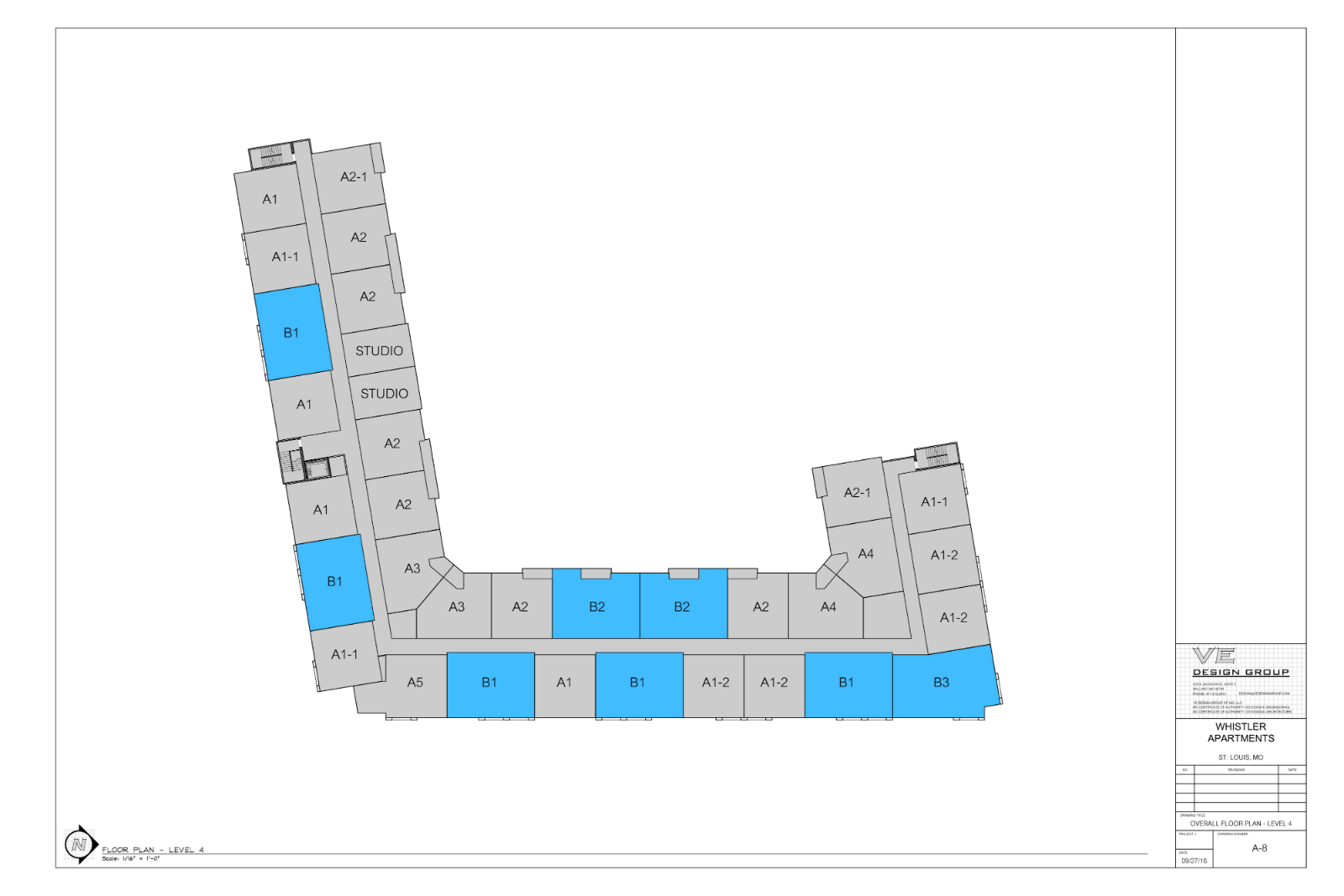

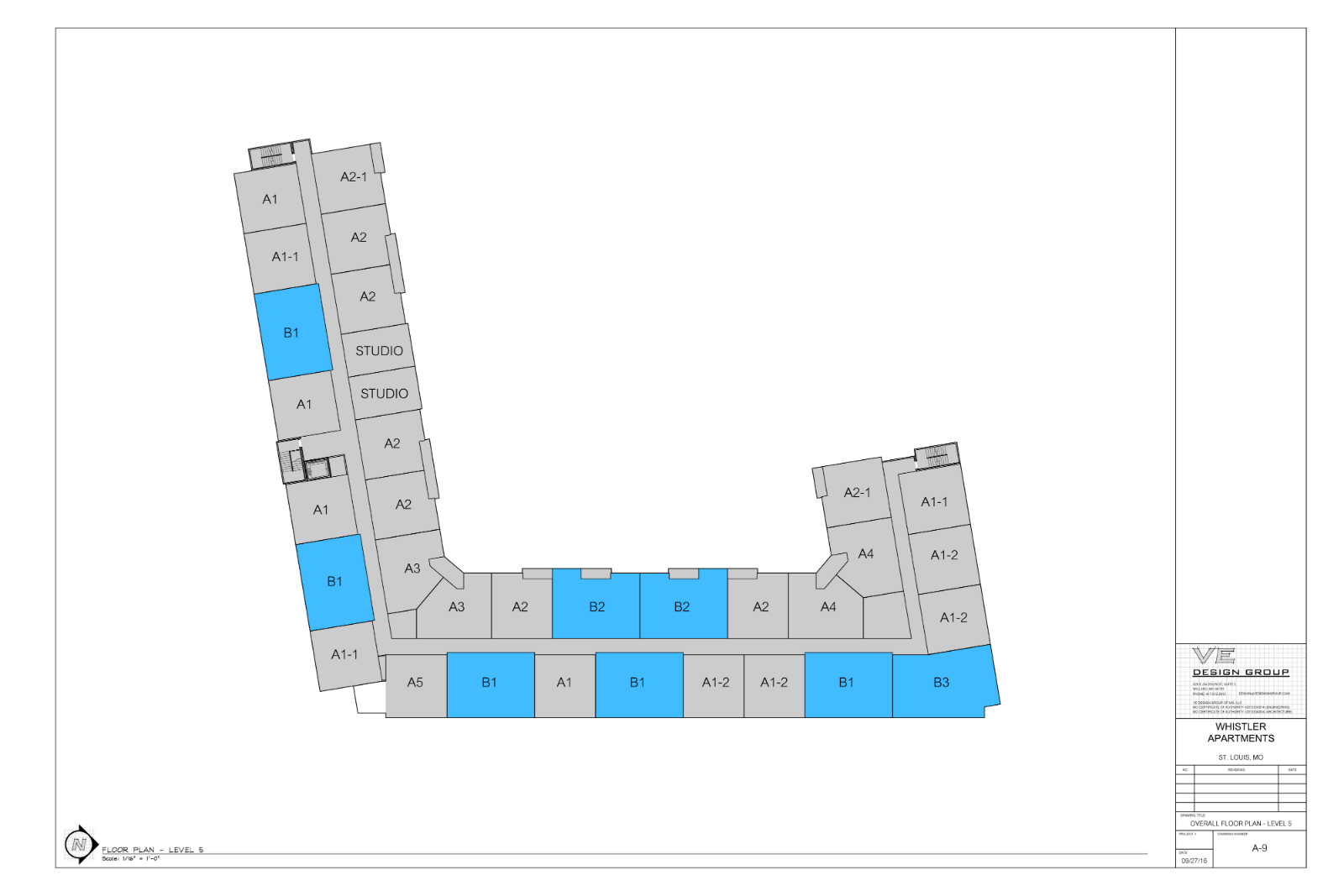

For their design for Forest Park Community College, Harry Weese and Associates and Dan Kiley envisioned a four-story complex arranged along two horizontal spines. Terraces and a sunken gathering space would tie the buildings together. Circulation would be by exterior walkways along the spine on the ground floor. These walkways would connect individual towers. Lecture halls were to be on the lower level, with labs on the top floor and classrooms and offices on the floors in between.

Kiley recently had finished his role with Eero Saarinen in designing the grounds of the Gateway Arch. For the college, he and Weese planned a series of courtyards connecting the spines at the western end of the campus. Trees would shadow the courtyards, the largest of which would step down to a large fountain, providing an exterior auditorium when dry.

A lawn to the north (facing Forest Park) would slope gradually down to a lake, which was never built. At the far eastern terminus of the spine, Tower A would stand atop a tall earthen berm. That berm and Tower A would jut out into the lake like Cahokia Mound rising above the flood plain. Across the lake would stand the theatre.

With the exception of the lake, much of the complex was built as designed. It has seen few alterations in half a century, with the exceptions of the ever growing surface parking lots to the south and the removal of some trees.

Weese’s structures float above a first floor of brick pilotis (piers) set on a concrete base. A fourth floor projects out from the mass of the building. Stair towers on the south side of the spine break up that facade, while the north facade accentuates the horizontal line of the complex. Weese designed bands of windows set back deeply from the brick facade, providing dramatic shadow lines. Perpendicular passageways pierce the spine at regular intervals, providing transparency through the brick spine. The red brickwork itself provides a texture and warmth not often seen in brutalist works from the period. Kiley intended his trees, once mature, further to soften the massing of the ensemble.

Together, Weese and Kiley created a modern center for public education that was simultaneously dense, urban and green. The master plan was approved in February 1965 and the initial building designs in June of that year. Rallo Construction and Kloster Construction built the complex. A spread in the Post-Dispatch on August 20, 1967 noted that between 4,000 and 5,000 students were inspected to enroll that fall, even though half the buildings were still under construction.

Thirty years after its construction, an article in Inland Architect extolled the design.

The student union, library, classroom and theatre buildings are models of how well buildings can be designed. Really virtuoso performances of structural/architectural spatial configurations, superb natural lighting and well-appointed materials, and the brick cladding is beautifully detailed.

Demolition for Towers A & B

Brutalism in architecture drew its name from the French brut—raw—referring to the raw or unfinished concrete surfaces favored my many mid-century architects. Even where brutalism adapted to other materials, it was typically massive in scale and sculptural in design. Brutalism was a reaction to the perceived frivolity of much modern design, a way of communicating the seriousness of architecture and of buildings and of the uses they serve. As such, brutalism found its most common expression in government and educational uses. But brutalism always had its detractors who perceived many such buildings as cold, totalitarian and … well … brutal.

After being maligned for decades, movements now are underway to preserve brutalist designs. In a culture that prioritizes the new, a 50-year-old design is often the most endangered. And Weese and Kiley’s design is now in its fifties. If the campus of St. Louis Community College—Forest Park is brutalism, then it is a very subtle, warm and humane brutalism. If you can look beyond the unfortunate parking lots and the bathrooms and fixtures that haven’t been updated in fifty years, the fact remains. Weese and Kiley’s design is stunningly good mid-century architecture.

In architecture, there are permanent buildings and then there are buildings that are disposable.

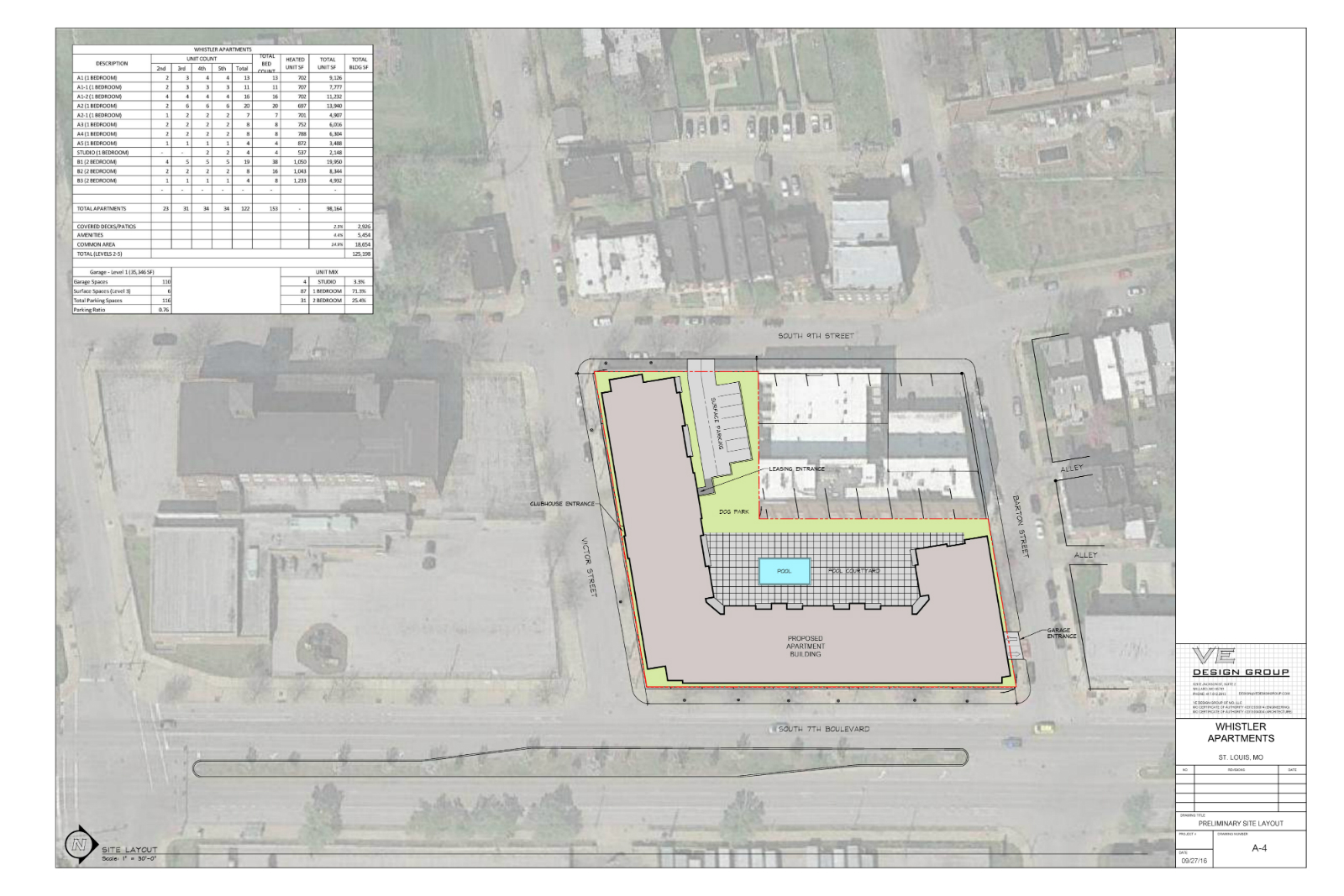

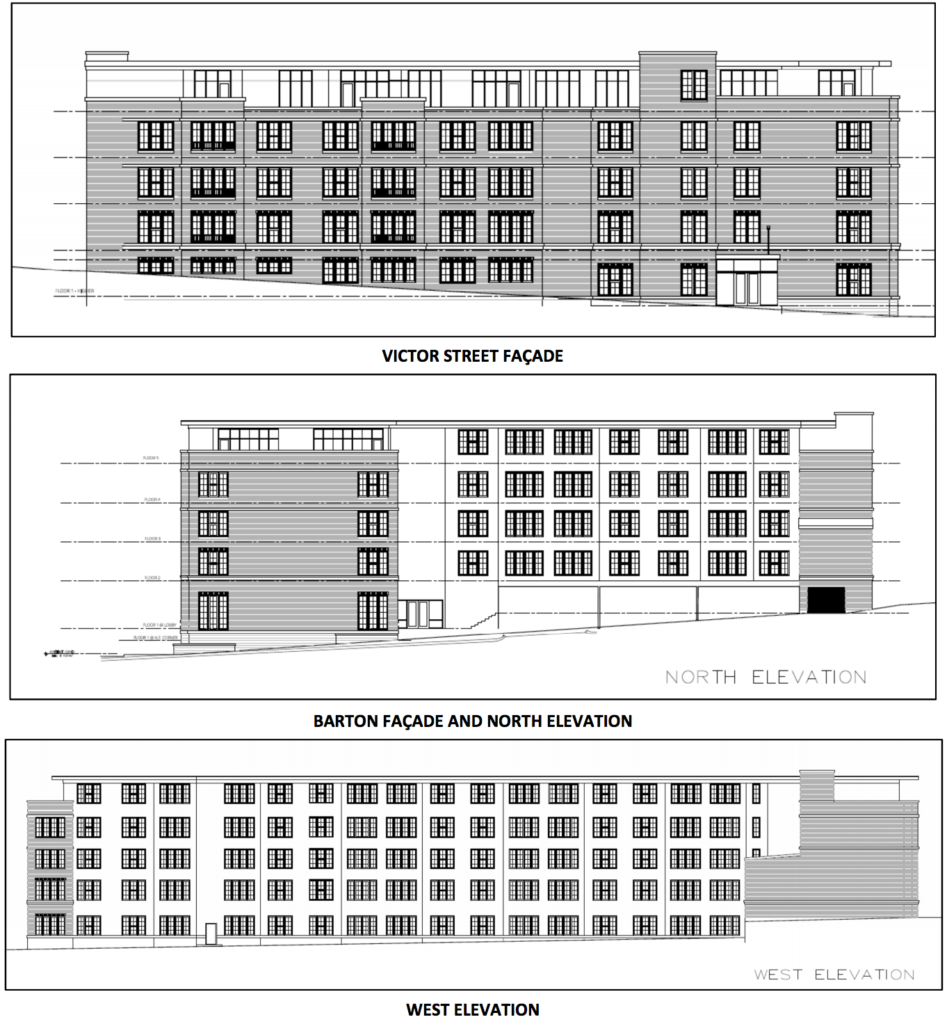

The school administration’s current plan is to build a $32 million 65,000 square foot Allied Health Building on Dan Kiley’s lawn facing Oakland Ave. The school will demolish Weese and Associates’ berm-topping Tower A—the most graceful in the complex—as well as Tower B. They will preserve the school’s surface parking lots.

In 1994, Weese and Kiley’s design for Forest Park Community College won the first ever 25-Year Award bestowed by the American Institute of Architects, St. Louis Chapter for buildings that have “withstood the test of time.” Twenty-three years after that award, the school’s leadership is seeking demolition.

Here we have the work of Harry Weese, that modernist who stood out for his advocacy to preserve our built history, and who simultaneously made history as one of the greats of modern architecture. And here we see a landscape by Dan Kiley, the father of modern landscape architecture. Here we see something permanent. And here we see plans to remove it for something disposable.

Notes:

1.https://placesjournal.org/article/the-architecture-of-harry-weese/

2.http://www.grahamfoundation.org/grantees/5086-creative-syncretism-the-early-architectural-works-of-harry-weese-columbus-indiana

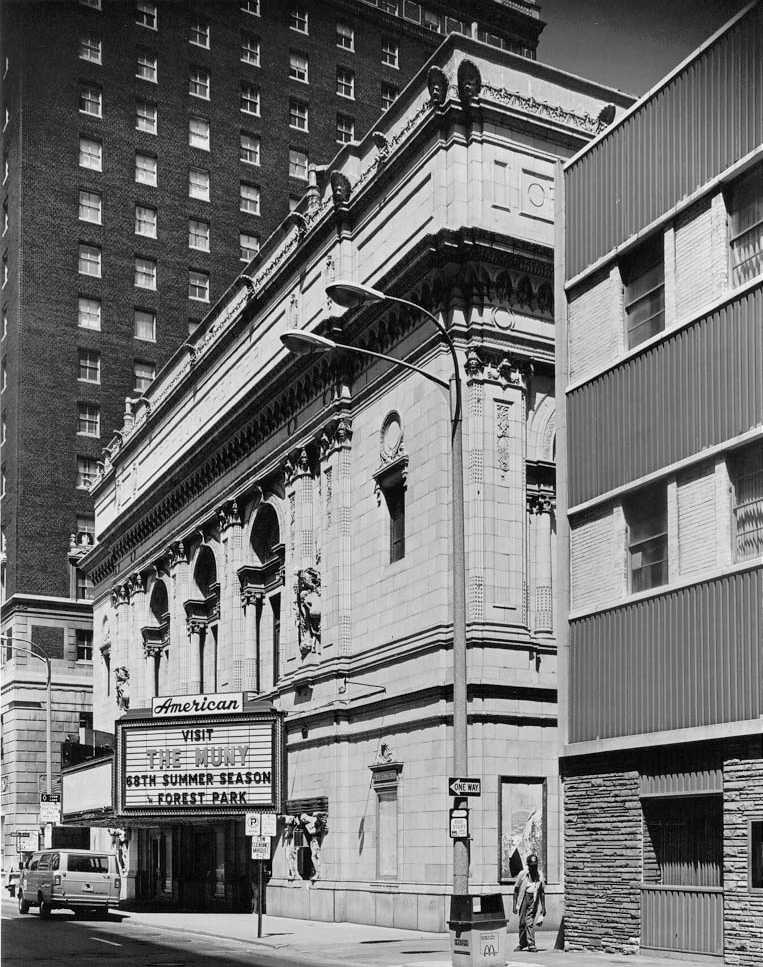

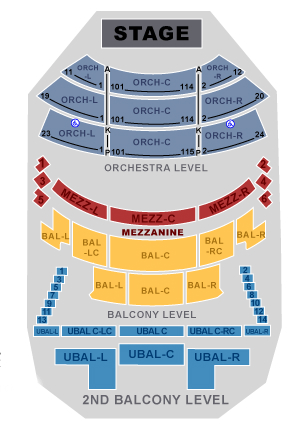

{the Orpheum Theatre c. 1920}

{the Orpheum Theatre c. 1920} The Beaux-Arts style Orpheum was completed in 1917 at a cost of $500,000. It opened as a vaudeville house and was later sold to Warner Brothers in 1930, operating as a movie theater until the 1960s. After a restoration in the 1980s, it reopened as the American Theater and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

The Beaux-Arts style Orpheum was completed in 1917 at a cost of $500,000. It opened as a vaudeville house and was later sold to Warner Brothers in 1930, operating as a movie theater until the 1960s. After a restoration in the 1980s, it reopened as the American Theater and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.