Author's posts

Feb 09

5 Things To Do This Weekend in St. Louis 2/10 – 2/12

Happy Friday! It’s time for another fun-filled weekend in St. Louis. If you are still pulling your plans together for the weekend, here are a few suggestions to help.

Orchid Show | February 9 – March 26

The annual Orchid Show offers visitors a once-a-year opportunity to see a rotating display of hundreds of orchids from the Garden’s expansive permanent living collection amid a tropical oasis inside the Orthwein Floral Display Hall.

Mardi Gras St. Louis: Cajun Cook off | February 11

Enjoy professionally prepared creole cuisine, live demos with samples, live music, and a fully stocked bar.

Science on Tap | February 11

This event will feature 80+ beer tastings, science demonstrations, live music and more! This total sensory experience will let you be hands-on with some of beer brewing’s most popular ingredients. Experience molecular gastronomy with your favorite beer, discover how buoyant your beer is and learn how Sam Adams Nitro technology works.

Live Music: Usual Suspects | February 11

The Usual Suspects formed in 1998 as a traditional jazz trio with piano, bass and drums. Having been influenced by so many other styles of music, it was evident early on that “traditional” was not the word to describe the music. Since 2000, the Usual Suspects has taken on many forms, from traditional and smooth jazz settings, neo-soul and R&B shows, to hosting and backing up spoken word events, and writing and recording original compositions. See them at Lumiere Place this Saturday.

Something Rotten! at the Fox Theatre | February 7 – 19

Set in 1595, this hilarious smash tells the story of Nick and Nigel Bottom, two brothers who are desperate to write a hit play. When a local soothsayer foretells that the future of theatre involves singing, dancing and acting at the same time, Nick and Nigel set out to write the world’s very first musical.

Make sure to share your St. Louis photos with us using #ExploreStLouis, you could be featured on our social page here. For more events, festivals and things to do in St. Louis, check out our events calendar.

The post 5 Things To Do This Weekend in St. Louis 2/10 – 2/12 appeared first on Explore St. Louis.

Feb 06

Hear this Week – Live Music in St. Louis February 6 – February 9

Live Music in St. Louis

St. Louis is the live music capital of the U.S., with scores of opportunities to catch great music every week! Here are just a few Bands of Note:

Monday, February 6 – Saxophonist Jeff Anderson & His Quartet take part in the Black History Month Concert at our own Webster University in Webster Groves. It features Bob DeBoo (bass), Adam Maness (piano), and Kaleb Kirby (drums). They start swinging at 7, $7.

Tuesday, February 7 – Over at Fubar, the Bunny Gang, which is fronted by Nathen Maxwell of Flogging Molly, plays not-so-Celtic rock. Reggae- and folk-influenced tunes come from this band’s new album “Thrive.” Doors open at 7, $15.

Wednesday, February 8 – Local jazz artist Kasimu Taylor brings his amazing trumpet work and fantastically tight trio to the Dark Room. Starts at 9, no cover.

Wednesday & Thursday, February 8 & 9 – Straight-ahead jazz pianist Bruce Barth and his trio stop by Jazz at the Bistro for two nights. This guy toured with Tony Bennett, so he’s the real deal. 7:30 both nights with a second show on Thursday at 11. Tickets start at $30.

Friday, February 9 – Local indie rockers Lightrider take the stage at Cicero’s in University City. Their music has been described as a mix of ambient post-rock, funk, jazz, and American pop rock. The all-ages show also features Oddsoul and the Sound and Casper Webs. Doors open at 7, $7.

What the Locals Know: Every Tuesday and Thursday night is karaoke night at the Just John, one of our town’s most popular gay and lesbian night clubs. The singing, good and otherwise but always fun, starts at 10pm. No cover.

Music Note of Note: The local jazz community lost a great musician and St. Louis native in December: Charles “Bobo” Shaw. Shaw was a member of the influential Black Artists Group, an arts collective that played and recorded here from 1968 to 1972. Born in 1947, this influential drummer also recorded and performed in New York City and Europe. Classically trained, he incorporated funk and new wave into his jazz drumming.

The post Hear this Week – Live Music in St. Louis February 6 – February 9 appeared first on Explore St. Louis.

Feb 02

5 Things To Do This Weekend in St. Louis 2/3 – 2/5

Happy Friday! It’s time for another fun-filled weekend in St. Louis. If you are still pulling your plans together for the weekend, here are a few suggestions to help.

St. Louis RV Vacation & Travel Show | February 2 – 5

In its 40th year, the St. Louis RV Vacation & Travel Show is one of the largest, public, recreational vehicle consumer shows in the country, consuming over 260,000 square feet of the America’s Center in downtown St. Louis. Attendees will see 300 RV’s highlighting the latest in state-of-the-art RV technology, streamline designs, parts and accessories as well as travel destination including campgrounds and resorts.

Morpho Mardi Gras | February 2 – March 31

Escape the cold by visiting Morpho Mardi Gras: Bugs, Butterflies and Beads! Bring your Krewe to the carnival during the months of February and March. Join the party at our Bug Parade, make a masquerade mask, and immerse yourself in a sea of blue as the Butterfly House floods the tropical conservatory with thousands of Blue Morpho butterflies. With the sounds of jazz in the air, inaugurate the season with these and other majestic creatures. This year, we will be featuring a larger-than-life glass Blue Morpho sculpture, by Craig Mitchell Smith.

NHL Centennial Fan Arena | February 3 – 5

This interactive traveling fan experience will visit the St. Louis Public Library in downtown St. Louis. The NHL Centennial Fan Arena is part of the NHL’s Centennial festivities honoring a century’s worth of extraordinary players, teams, remarkable plays and unforgettable moments. Attendees can experience a mobile hockey museum, VR Zamboni and the Stanley Cup.

Owls Prowls | February 4

Come over to the dark side and meet those amazing birds that exist by moonlight. Owl Prowls at the World Bird Sanctuary offer an exciting opportunity to learn more about the amazing life of owls. Spend an evening with a WBS naturalist who will introduce you to live owls and their unique calls. Then, take an easy night hike through our grounds to try to call in a wild owl!

Monster Jam at The Dome at America’s Center | February 4

Monster Jam® is the most action-packed live event on four wheels where world-class drivers compete in both monster truck racing and freestyle competitions. Celebrating 25 years of adrenaline-charged family entertainment, Monster Jam combines spontaneous entertainment with the ultimate off-road, motorsport competition. Monster Jam features the most recognizable trucks in the world including Grave Digger®, Max-DTM, El Toro Loco®, Monster Mutt® and many more.

Make sure to share your St. Louis photos with us using #ExploreStLouis, you could be featured on our social page here. For more events, festivals and things to do in St. Louis, check out our events calendar.

The post 5 Things To Do This Weekend in St. Louis 2/3 – 2/5 appeared first on Explore St. Louis.

Jan 31

St. Louis, Entrepreneurial Boomtown

Back in the mid-oughts, Jarret Glasscock was happily ensconced at the Genome Sequencing Center at Washington University in St. Louis, working on the federal government’s Human Genome Project. He and his fellow scientists were exceptionally good at what they did: they could sequence the DNA of a cell for about 1/100,000th the cost of traditional methods. Pharmaceutical companies soon came knocking on their door with contract offers to do DNA sequencing for drug development purposes. But the center was busy fulfilling government grants and kept turning the offers down. After a few years of this, says Glasscock, “we finally got it through our thick skulls that maybe there’s a need for some kind of company to exist.”

So, in 2008 Glasscock and a few colleagues pulled together whatever money they could, rented a former photographer’s studio downtown off Craigslist for $700 a month, and filled the office with half a million dollars’ worth of used genetic sequencing machinery—which they cleverly managed to convince the company that sold it to them to finance. Pretty soon, their new company, Cofactor Genomics, was making money. They hired more staff, bought better equipment, and briefly made international news when they helped map the genome of heavy-metal icon Ozzy Osbourne.

Eventually, Glasscock became the company’s CEO and the firm moved to its current digs, a squat brick industrial building in Midtown St. Louis that backs up to Interstate 64. A metal coatings factory sits on one side; on the other, across a vast empty parking lot, a giant grain elevator looms.

Inside, the décor is contemporary high tech with a slight midwestern twist. It’s mostly one big open space, with a couple of glassed-in conference rooms with math equations scrawled on the panes. Two ski lift gondolas, bought for $800 each from a resort in Wisconsin, are available for more intimate meetings. On a wall is a vintage sign that reads “Gun Shop” next to a picture of a revolver. The barrel of the gun points toward the back, where the gene sequencing lab is located behind closed doors secured with push-button combination locks—a precaution demanded by Cofactor’s pharmaceutical industry clients, who are serious about protecting their intellectual property. In a corner by the back door is a drum set and some old bikes the company’s eighteen employees can use to go to lunch. There haven’t been many places to eat in this aging industrial part of Midtown. But more and more restaurants and coffee shops are popping up to cater to the 150 startups now occupying several rehabbed buildings in the neighborhood, which has been renamed the Cortex Innovation Community.

Cofactor is now being feted by the kind of West Coast venture capital investors who, a decade ago, would never have thought to put money into a St. Louis startup. The firm’s leaders were invited to spend last summer networking at Y Combinator, the famed Mountain View seed fund that nurtured Airbnb and Dropbox. In February, Cofactor acquired a San Francisco–based competitor, Narus Biotechnologies.

To many Americans, St. Louis is known for urban dysfunction and slow economic decline. It was in the nearby suburb of Ferguson in 2014 that riots broke out after a white police officer shot an African American teenager. St. Louis is one of those places where every year or two another big homegrown company seems to get bought by outside owners: aircraft maker McDonnell Douglas in 1997, food processor Ralston Purina in 2001, May Department Stores in 2005, brewer Anheuser-Busch in 2008. As this magazine recently reported (see Brian S. Feldman, “The Real Reason Middle America Should Be Angry,” March/April/May 2016), as a result of changes in federal antitrust and other competition policies, the number of Fortune 500 companies located in St. Louis has shrunk from twenty-three in 1980 to nine today.

Growth industry: Kristine Menn, greenhouse coordinator for the St. Louis-based renewable fuel startup Arvgenix, works on a field pennycress flower in the Danforth Plant Science Center.

But as the story of Cofactor Genomics illustrates, a city that has lost so many big old companies is becoming home to a lot of small new ones. Last year, Popular Mechanics deemed St. Louis to be one of the fourteen best startup cities in America, and in January of this year, Business Insider said it had the “fastest-growing startup scene” in the country.

St. Louis is a long way from becoming another Silicon Valley. But its sudden emergence as a hotbed of entrepreneurship holds lessons for a country struggling to make a growing economy benefit Americans who don’t happen to live in a handful of booming coastal megalopolises. For decades, St. Louis followed the familiar economic development playbook: try to attract big out-of-town companies, or keep local ones from leaving, by showering them with tax breaks and other subsidies. While it hasn’t exactly abandoned that old strategy, St. Louis has increasingly shifted to a new one of attempting to grow its own small firms. Metro areas across the country are trying to do the same, in many cases with little to show for their efforts. St. Louis seems to have hit on the right formula, though actions in Washington could determine whether, over the long term, it succeeds or fails.

While it may be hard for people who think of St. Louis as part of “flyover” country to wrap their heads around the idea of it as a startup haven, the numbers don’t lie. Business creation in St. Louis has risen every year since 2009, jumping 18 percent from 2012 to 2013, a year business creation actually fell nationally. In 2006, St. Louis was 11 percent below the national average in the number of new firms per 100,000 people. By 2012, St. Louis had narrowed this “startup density” gap to only 3 percent, according to the Kauffman Index of Entrepreneurship. St. Louis now ranks twenty-sixth among the top forty metro areas by startup density, ahead of some cities that garner lots of attention for their entrepreneurship scenes, like Pittsburgh, Columbus, and Philadelphia.

St. Louis’s startup scene is most noticeable in the information technology sector, led by such firms as the social media company LockerDome and app developers RoverTown and Aisle411. Venture capital companies poured $176 million into area IT startups in 2015, up from $66 million in 2013, according to the St. Louis Tech Startup Report. That is roughly double the figure of Kansas City, a region of a similar population on the other side of the state. St. Louis tech startups employed more than 1,400 people in 2015, up from less than half that in 2011. In 2015, three new accelerators started in St. Louis, and three new venture capital funds entered the fray.

But it’s not just IT and biotech startups that are flourishing. New St. Louis firms are popping in sectors like education, food, and—in the longtime home of Budweiser—craft beer.

The roots of St. Louis’s startup boom go back to the late 1990s, when a group of political and business leaders, frustrated with the metro area’s slow economic growth, began studying how other old industrial cities, such as Boston, were turning themselves around. They concluded that St. Louis had the necessary resources—highly ranked universities, med schools, and hospitals, plus major research-focused agricultural firms like Ralston Purina and Monsanto—to become a hub of life science startups. This precipitated the creation of a number of economic organizations that today form a kind of infrastructure for entrepreneurial activity: new investment funds, incubators for companies, new workforce programs.

Two organizations were especially critical in these early years. One was the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center, which opened in 2001 with funding from Monsanto and the Danforth Foundation (William H. Danforth was the founder of Ralston Purina). It has quickly grown into a world-renowned research facility, attracting tens of millions of dollars in federal grants annually to support hundreds of plant scientists. These scientists work directly with ag-tech startups developing new strains of crops that have, say, higher nutrition value, or better capacity to withstand the droughts that come with climate change. The center also cofounded the Ag Innovation Showcase, which has become the premier event in the nation around agricultural technology and innovation.

The other key institution was the Skandalaris Entrepreneurship Program at Washington University, begun in 2001 and expanded in 2003 with a grant from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Renamed the Skandalaris Center for Interdisciplinary Innovation and Entrepreneurship, it became a hub of entrepreneurial training and networking, with a mentoring program for budding area entrepreneurs that has proved invaluable.

To many Americans, St. Louis is known for urban dysfunction and slow economic decline. In fact,Business Insider says it has the “fastest-growing startup scene” in the country.

But by 2008, all this activity still wasn’t generating much in the way of actual economic outcomes. This was partly a result of the inherent cycles of research and development and commercialization in the sectors St. Louis chose to stress. It takes longer to build a plant science company than a new mobile app startup. Then the Great Recession hit, shrinking St. Louis’s per capital personal income by 5 percent that year and eventually driving the metro unemployment rate to over 10 percent. Worst of all, 2008 was also the year that multinational brewing giant InBev acquired Anheuser-Busch, the corporate crown jewel of St. Louis, and laid off hundreds at its South St. Louis headquarters.

That same year, a former telecommunications manager and entrepreneur named Jim Brasunas had an idea. Brasunas had lived in St. Louis since 1994 and been involved with several technology companies, including running an incubator in downtown St. Louis. In his dealings with tech entrepreneurs around the region, he discovered that they all felt alone in their attempts to build successful companies there. They didn’t know other up-and-coming entrepreneurs in the same sector, or have successful older ones they could turn to for advice. Brasunas also learned that area investors looking to put money into IT startups had no idea that there were any such firms in St. Louis. Sometimes an entrepreneur and an investor would be on the same flight to San Francisco to talk to venture firms, utterly unaware of each other’s presence. “After hearing the same story twenty-five or thirty times, I just started getting these people together casually,” says Brasunas. In 2008, he formalized this network by starting a nonprofit organization, the Information Technology Entrepreneurs Network (ITEN).

To get his operation off the ground, Brasunas applied for funding from the Missouri Technology Corporation (MTC), a public-private investment fund controlled by the state government and championed by Governor Jay Nixon. The MTC’s very existence was another example of the change in thinking that was occurring about how to jump-start economic growth. As in just about every other state and municipality in the country, Missouri’s strategy had long been to throw tax dollars at big, footloose corporations. It’s a popular practice with voters and politicians, affording the latter the opportunity to hold press conferences to announce that they’ve lured a new corporate headquarters to the area or kept an existing one from leaving. But in terms of actually boosting net economic activity, it’s a mug’s game. A study by the researcher Nathan Jensen found that St. Louis–area companies receiving Missouri state tax incentives have actually performed worse in terms of creating jobs than companies elsewhere in Missouri that didn’t receive incentives.

The MTC’s modest initial grant to ITEN in 2008, plus later expansion grants, turned out to be wise (the Kauffman Foundation also supported ITEN). Over the next eight years, ITEN helped catalyze the entire entrepreneurial ecosystem in St. Louis. Today, many entrepreneurs and others give a huge amount of credit to Brasunas and ITEN for building connections and thus creating a new network of entrepreneurial support. Indeed, Yasuyuki Motoyama, in a paper coauthored with Karren Watkins at Washington University, points out that the “connections between novice and experienced entrepreneurs” that ITEN facilitated are probably the single-biggest factor in St. Louis’s entrepreneurial emergence.

For decades, St. Louis followed the familiar economic development playbook: try to attract big out-of-town companies with tax breaks and other subsidies. It has increasingly shifted to a new one of attempting to grow its own small firms.

Three years later, the MTC made another shrewd bet: it put seed money into a new program, called Arch Grants, with a model for economic development unlike any in the country. The organization runs a global competition to identify potential entrepreneurs from virtually any industry sector. It then provides those with the most promising business plans $50,000 equity-free grants and pro bono support services if they agree to build their businesses in St. Louis. Even more important than the money, Arch Grants helps these emerging entrepreneurs connect with each other—building bonds not unlike those among a class of college freshmen—and plugs them into St. Louis’s increasingly thick and energized network of entrepreneurs, funders, work spaces, and social events.

By 2013, all of this activity was bearing fruit. That year, the St. Louis Regional Entrepreneurship Initiative Reportreleased an analysis of entrepreneurial activity and deal flow. According to the report, in 2007 only eleven companies reached “validated startup status.” (This was judged to be when a company reached milestones such as going through an accelerator, receiving equity investment, completing an intellectual property license, and so on.) By 2012, forty-two companies had become validated startups.

Importantly, the composition of startups receiving equity investments had changed significantly. In 2006, two-thirds of investments went to bioscience companies; only a quarter went to tech startups. This reflected the orientation of official economic development efforts in St. Louis. Yet by 2012, the situation was precisely reversed: tech firms received two-thirds of equity investments, and bioscience companies accounted for one-quarter.

Entrepreneurship has also found its way into the old corporate heart of the region: beer. Schlafly, a craft brewery that has been around for twenty-five years, has experienced strong growth and, earlier this year, announced it was doubling annual production to meet demand. Just within the last few years, more craft breweries have followed: O’Fallon Brewery, Urban Chestnut Brewing, and Senn Bierwerks, which will open in 2017. Oh, and don’t forget about the William K. Busch Brewing Co., founded in 2011 by the great-grandson of Adolphus Busch, cofounder of Anheuser-Busch.

In some ways, St. Louis is not unique. What we call “startup fever” has swept the country over the last several years, with cities of all sizes creating accelerators, incubators, pitch competitions, and all sorts of other programs intended to boost entrepreneurship. Pittsburgh, for example, has been celebrated for its entrepreneurial renaissance, with recognition from various “best places to start” rankings, and an increase in venture funding, new incubators, state programs, and more. Similar to Washington University’s role in St. Louis, Carnegie Mellon has played a catalytic role in Pittsburgh entrepreneurship. And yet, by other measures, this activity has yet to translate into entrepreneurial outcomes. In 2014 and 2015, Pittsburgh ranked last among large metro areas on the Kauffman Index, with the lowest rate of new entrepreneurial entry, the second-lowest startup density, and even one of the lowest rates of “opportunity” entrepreneurship. A similar story might be told of cities such as Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia.

What, then, is St. Louis doing differently that might explain its relative success? In a recent article in the journalInnovations, Ken Harrington, who led the Skandalaris Center for over a decade and has been closely involved in the St. Louis startup scene, argues that the secret sauce was “connectivity.” In the past, St. Louis was not without entrepreneurial energy, according to Harrington, but it existed in disconnected pockets. This stymied the formation of an “entrepreneurial genealogy” that occurs when successful entrepreneurs from one generation become the next generation’s mentors and investors. This genealogy is a distinguishing characteristic of places like Silicon Valley.

Home is where the lab is: Cofactor moved from a former photography studio to its current headquarters, which sits across from a grain elevator.

A metro area without this genealogy needs to create it by bringing together the disconnected pockets. It’s faddish in economic development circles today to talk about collisions. If you create lots of bars and coffee shops and parks, serendipitous unexpected connections will occur: the strategy is premised on people literally running into each other.

But that’s not what happened in St. Louis. Instead, organizations such as ITEN, the Skandalaris Center, and Arch Grants came into being and intentionally and deliberately built connections and networks.

A good example of how this connectivity can work is RoverTown, a startup that provides student discounts through a mobile app. After receiving an Arch Grant in 2013, the company moved to St. Louis from Carbondale, Illinois. It relocated to the T-REX, a nonprofit co-working space downtown, went through an accelerator program called Capital Innovators, and received a follow-on Arch Grant. It then took part in another program run by ITEN called Mock Angel, which prepares entrepreneurs to make their pitches to equity investors, and secured nearly a million dollars in funding last year. In 2014 it was named the fastest-growing tech startup in St. Louis.

RoverTown is not small-time—they have a satellite office in Chicago, and two VPs of GrubHub are on the board. They are in St. Louis by choice.

RoverTown’s experience also illustrates another side of St. Louis connectivity. One of its investors is Tom Hillman, a serial entrepreneur who formerly owned Answers.com, a leading IT firm based in St. Louis. Hillman has become a central figure in St. Louis entrepreneurship and philanthropy, and embodies the new entrepreneurial genealogy that has developed in the region.

St. Louis’s recent success at fostering startups shouldn’t be all that surprising. The metro area has had most of the ingredients for a long time: a central location, great universities, large sophisticated corporations, an educated workforce, world-class cultural institutions (symphony, art museum, zoo, botanical gardens), suburbs with good schools, and city neighborhoods full of beautiful old homes available at affordable prices. (Okay, yes, St. Louis is very humid in the summer.)

Several key ingredients, however, were only added relatively recently. The first was a change in mentality of the leadership class at the city, metro, and state levels. These folks—elected officials, university presidents, old money muckety-mucks—needed to be persuaded that the traditional ways of trying to foster growth (bribing big companies with subsidies, pouring endless tax dollars into downtown redevelopment projects) weren’t working, and that giving some attention and public and philanthropic resources to fostering startups might. Crucially, the new mentality needed to be shared by executives at the big locally based corporations who have an interest and the autonomy to participate in local civic life. The Danforth Center couldn’t have been built without the help of Monsanto, for instance, and its renewable fuels program is funded by the family that owns St. Louis–based Enterprise Rent-A-Car. In 2015, ITEN launched a corporate engagement program in which startups and large corporations will interact in a variety of ways, including “reverse pitches,” in which the corporations pitch their ideas and needs to startups. Initial corporate partners included Monsanto, the Reinsurance Group of America, and Enterprise.

The second missing ingredient was connectivity. Fortunately, St. Louis had civic entrepreneurs like Jim Brasunas, Ken Harrington, and the founders of Arch Grants, who figured out how to increase the connections among people and institutions in ways that make an entrepreneurial scene gel and grow.

Challenges remain, of course. Despite all the energy and excitement, there’s no point at which the startup scene in St. Louis is “finished” or “complete.” Nearly everyone we have talked to agrees that St. Louis faces a challenge in sustaining today’s entrepreneurial momentum.

Policymakers in Washington could make the city’s job easier—or harder. Many of St. Louis’s most promising startups, especially in the biotech and ag-tech sectors, would never have been started and could not continue absent federal investments in medical and agricultural research. Cofactor Genomics is a perfect example. CEO Jarret Glasscock got his training while working on the federally funded Human Genome Project. Contracts from the NIH and the USDA make up a significant portion of the firm’s revenue. Federal tax credits covered some of the cost of its new building and equipment. In general, more federal funding for these programs would help St. Louis, and cuts would hurt.

The federal government can also help places like St. Louis by remaining economically open and engaged with the rest of the world. Because of the Danforth Center and organizations like BioSTL, a university-led seed investment fund, St. Louis has become a global center of plant sciences, attracting new entrepreneurial companies to the area. Earlier this year, an Israeli company, NRGene, announced that it was establishing its U.S. headquarters in St. Louis—impressively, it is the fourth Israeli plant science company to set up its base in the city in the last two years. If our next president insists on alienating the rest of the world, you can bet that the flow of foreign entrepreneurs into St. Louis and other cities will slow, if not cease altogether.

Sometimes a St. Louis entrepreneur and an investor would be on the same flight to San Francisco to talk to venture firms, utterly unaware of each other’s presence.

Better parental leave policies from the federal government could also help by making it possible for more women to follow their entrepreneurial dreams. St. Louis, like other cities, faces a gender imbalance in terms of participation in the startup scene. Motoyama and Watkins found that men make up 70 to 80 percent of the people who participate in many of the city’s entrepreneurship support organizations. In the United States as a whole, business ownership has fallen among men and remained stable among women, as women make up a large and growing share of the workforce, especially the educated workforce.

More could also be done to open up opportunities for minorities. The talent is certainly there: World Wide Technologies—the nation’s largest black-owned business, according to Black Enterprise magazine—is based in St. Louis. Yet minorities are underrepresented among the new crop of St. Louis startups.

Financing is another area where federal policymakers could extend help to entrepreneurs. While St. Louis has seen an increase in equity investments into startups, most new businesses (including tech firms) do not receive equity financing. Instead, they seek out various forms of credit from banks: loans, lines of credit, credit cards, leasing, trade credits, and so on. Young and small firms, moreover, seek credit from small banks and credit unions at higher rates than large companies do. Yet small banks—including black-owned banks—were hit hard by the financial crisis. Some went under; others were acquired by larger banks that took advantage of decades-old federal deregulatory decisions, a phenomenon that continues to shrink the ranks of small lenders. New federal regulations put in place since the financial crisis have reinforced the advantages

of bigness.

Indeed, arguably the single-biggest favor the federal government can do for St. Louis’s startup scene is to change its policies on antitrust enforcement. For more than thirty years Washington has allowed corporate mergers and acquisitions to take place largely unimpeded, to the point where a handful of huge companies dominate market after market. Most of those behemoths are located in places like New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and LA. And most startups today, especially in the technology fields, never expect to grow their companies, but instead hope to get bought out by one of the big boys. This makes for a useful “exit strategy” for investors. But it also leads to less competition: startups seldom get big enough to challenge the incumbents. And it means that smaller cities like St. Louis that have painstakingly nurtured startups are likely to see most of them skip town after getting gobbled up by the Googles, Facebooks, and Pfizers of the world. In that scenario, instead of competing in the big leagues, St. Louis would become an uncompensated farm team for San Francisco and Boston.

This is the world today as we find it. But it is not necessarily the one that entrepreneurs would prefer. Asked if he expects Cofactor Genomics to be acquired, Glasscock replies, “Interesting question. That’s been the thinking of our board from the beginning.” On the other hand, he says, he loves living in St. Louis (he’s originally from Arizona), loves the corporate culture he and his colleagues have created, loves the challenge of steering the ship. “I can definitely imagine us having 500 employees ten years from now,” he says, with a noticeable twinkle in his eye.

Dane Stangler is vice president of research and policy at the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Colin Tomkins-Bergh is a research analyst for the foundation.

Jan 31

St. Louis is the New Startup Frontier

In 2013, when I was a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, I flew to St. Louis to learn about the city’s budding startup scene. The city, like the rest of the U.S., was stuck in a decades-long entrepreneurial slump that had left its economy dependent on a handful of big, staid corporations — corporations that were pulling up stakes to head overseas at a rate that alarmed local leaders. (The city’s iconic brewer, Anheuser-Busch, had been sold to a Belgian conglomerate five years earlier.) But an informal coalition of local business leaders, wealthy investors and ambitious 20-somethings weretrying to spark an entrepreneurial revival in the Arch City. They had launched a fund to invest in local ventures, created entrepreneurship clubs at local universities, and converted part of a massive downtown office building into an unlikely startup hub.

I was impressed by the group’s enthusiasm but skeptical of its prospects. Countless cities had tried similar strategies — “incubators,” “accelerators,” venture funds, tax breaks — in an effort to capture some of Silicon Valley’s elusive magic. Few had succeeded.

But maybe my skepticism was misplaced. Data from the Census Bureau released last week showed that in 2014, 9.7 percent of the businesses in the St. Louis metro area were startups less than a year old, up three percentage points from 2009. Only Elizabethtown, Kentucky, saw a bigger increase during that period. In just five years, St. Louis rolled back 15 years of decline in its local startup rate.

The news is grimmer in the country as a whole. The national startup rate fell in 2014 for the second straight year, to 8 percent. The rate at which Americans start businesses has been falling for more than three decades, and while the decline has slowed in recent years, it has shown no sign of reversing. The trend worries economists because new businesses play a vital role in creating jobs, improving productivity and spurring economic growth; some researchers believe the decline in entrepreneurship, and in other measures of economic dynamism such as labor mobility, could be part of the reason the U.S. has experienced such a slow bounceback from the past two recessions.

Over the long term, the decline in entrepreneurship has been strikingly universal, cutting across industries and regions. But as the St. Louis example shows, some areas are seeing signs of progress. From 2009 to 2014, the startup rate rose in about a third of U.S. metro areas and 12 of the 50 states, with Missouri leading the way. Three of the five most-improved cities were in Missouri — St. Louis, Springfield and St. Joseph — and Kansas City was number 12.

| NEW BUSINESSES IN 2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| METRO AREA | TOTAL | SHARE OF ALL BUSINESSES | CHANGE IN SHARE SINCE 2009 | |

| 1 | Elizabethtown, KY | 179 | 9.0% | +4.3 |

| 2 | St. Louis, MO-IL | 4,876 | 9.7 | +3.0 |

| 3 | Bowling Green, KY | 217 | 9.1 | +2.5 |

| 4 | Springfield, MO | 826 | 9.6 | +2.0 |

| 5 | St. Joseph, MO-KS | 171 | 7.5 | +1.8 |

| 6 | Odessa, TX | 220 | 7.5 | +1.5 |

| 7 | Victoria, TX | 145 | 6.1 | +1.3 |

| 8 | Manhattan, KS | 132 | 6.1 | +1.3 |

| 9 | Tallahassee, FL | 528 | 7.9 | +1.2 |

| 10 | Bismarck, ND | 224 | 7.3 | +1.2 |

| 11 | San Angelo, TX | 180 | 8.0 | +1.2 |

| 12 | Kansas City, MO-KS | 3,027 | 8.4 | +1.1 |

| 13 | Redding, CA | 203 | 6.2 | +1.1 |

| 14 | Lexington-Fayette, KY | 681 | 7.5 | +1.1 |

| 15 | Columbus, IN | 71 | 4.9 | +1.1 |

| 16 | Naples-Marco Island, FL | 834 | 9.9 | +0.9 |

| 17 | Burlington-South Burlington, VT | 341 | 6.5 | +0.9 |

| 18 | Pine Bluff, AR | 67 | 5.1 | +0.9 |

| 19 | State College, PA | 152 | 5.9 | +0.9 |

| 20 | Racine, WI | 178 | 5.7 | +0.9 |

On the one hand, it isn’t surprising to see Missouri making progress. Both the state’s public and private sectors have been unusually aggressive in promoting entrepreneurship. The state has its own investment fund, theMissouri Technology Corporation, which invests in local businesses; the fund, together with newly formed private investment groups, have helped the state emerge as a regional leader in startup financing. The Kauffman Foundation — a prominent nonprofit that researches and promotes entrepreneurship — is based in Kansas City.

But it’s hard to know whether those efforts — or those of local boosters in St. Louis — are what’s making a difference. That’s partly because the limited data on entrepreneurship makes it hard to study the impact of government policies. Reliable data on business creation and destruction, even at the national level, has only been available for the past few years; until relatively recently, economists didn’t even know that the startup rate was declining. Even now, the measures are crude, making it hard to distinguish a fast-growing startup from a local mom-and-pop store.

Our knowledge is improving, however. Earlier this month, the Census Bureau, in a joint effort with the Kauffman Foundation, released the firstAnnual Survey of Entrepreneurs, which provides new information on America’s businesses and the people who found them. The report’s most valuable insights will come in future years, as trends become clear, but even the first year’s data contains interesting nuggets. For example, by far the largest share of new businesses in Missouri — nearly a third — are in health care, an area the state has actively promoted. Also interesting: Women own a higher share of startups in Missouri than in any other state. That could be a hint that one way to help turn America’s entrepreneurial slump around is to help more women to start businesses.

“What we’re seeing is a lot more gender and ethnic diversity in our newer businesses than we had in our older businesses,” Secretary of Commerce Penny Pritzker, herself a former entrepreneur, said in an interview. “This is the kind of information that is really vital for policymakers.” Armed with better data, perhaps leaders in both the public and private sectors will at last crack the code for promoting entrepreneurship — and reverse the startup slump in the process.

Hunger in America

Here’s some welcome news: Fewer Americans, and particularly fewer children, are going hungry. According to data released by the Agriculture Department this week, 15.8 million U.S. households, or 12.7 percent, experienced “food insecurity” at some point in 2015, meaning their access to food was limited by financial or other constraints. That’s a big improvement from 2014, when 14 percent of households were food insecure, and from 2011, when the food insecurity rate neared 15 percent in the wake of the Great Recession. The share of households that experienced actual hunger — what the government calls “very low food security” — fell too, though not quite as quickly. Children went hungry in 274,000 households at some point during the year.

Hunger rose during the recession and has been slow to decline in the recovery. The issue has at times become a political cudgel — just Google “Obama” and “food stamps,” or, better yet, don’t — but this week’s report shows the pace of improvement is finally starting to accelerate. That’s just the latest sign that with unemployment falling below 5 percent, the economic recovery is starting to reach some of the most vulnerable American households.

Slower growth

The jobs report earlier this month showed that U.S. employers added 151,000 jobs in August, a solid though somewhat disappointing number. But on Wednesday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics said that pretty much all of those jobs will effectively disappear from the data when it revises its numbers early next year.

Hold on, Jack Welch, don’t go trumpeting any conspiracy theories quite yet. The announcement was part of a standard annual process of “benchmark revisions.” The monthly jobs figures are based on a survey of businesses, which is the only way to make estimates available in a timely manner. But the government also collects a much more precise count of the jobs in the economy via state unemployment insurance records. Every year, it reconciles the survey-based numbers with the more reliable unemployment records and makes whatever adjustments are necessary.

This year’s adjustment is relatively small by historical standards. According to a preliminary estimate from the BLS, there were 150,000 fewer jobs in the U.S. as of March than previously believed. That’s a downward revision of 0.1 percent, smaller than the 0.3 percent average adjustment over the past decade and much too small to change our understanding of how the economy as a whole is doing. By far the biggest revision, on a percentage basis, came in the mining sector, which isn’t surprising; the oil and gas industry, which is part of the mining sector, has been extremely volatile in the past year due to tumbling oil prices. That kind of volatility can be hard to track in real time.

The week ahead

Hiring is up and unemployment is down, but as of 2014, Americans still weren’t making any more money: Median household income has beenessentially flat since the recession ended in 2009. This week, we’ll learn whether 2015 was the year that finally began to change. On Tuesday, the Census Bureau will release its annual report on income and poverty in the U.S. and the individual states.

It’s likely the report will show at least some increase in household income in 2015. Sentier Research, a private firm working with publicly available government data, estimates median incomes began to rise in mid-2014 and are now essentially back to where they when the recession began nearly nine years ago, after adjusting for inflation. Even if Sentier is right, however, it is unlikely that the poverty rate is anywhere close to its prerecession level. The U.S. poverty rate was 14.8 percent in 2014, up from 12.5 percent in 2007.

Elsewhere

Scott Patterson, John W. Miller and Chuin-Wei Yap of The Wall Street Journal tell the remarkable tale of a Chinese billionaire who stockpiled 77 billion beer cans’ worth of aluminum in the Mexican desert.

Inequality is up in the U.S. — that’s well-known. But the picture looks different from one state to the next. Quoctrung Bui of The New York Times charts the trends and finds some interesting patterns.

State and local governments aren’t the only ones that spend public dollars to build private sports stadiums — the federal government does, too. And it’s every bit as bad an idea as it sounds, according to new research from Ted Gayer, Austin J. Drukker and Alexander K. Gold of the Brookings Institution.

Derek Thompson of The Atlantic interviews Economist columnist Ryan Avent about his new book on how technology is reshaping the global labor force.

Article courtesy of Ben Casselman at FiveThirtyEight, see the original story here.

Jan 31

The Right Way to Build a Tech City

Startups should know what differentiates their product from others. Building around an unique strength, a facet that’s difficult to emulate, offers small companies a chance to gain critical mass. New companies should focus on a strength and own one particular piece of their market. Startups that fail to do this can quickly become commodities.

The same can be said for cities and regions looking to make themselves into destinations for tech. Simply trying to emulate the Bay Area and its vast net of tech-related disciplines makes for an impossible task. As I wrote about Chicago and its tech ecosystem recently, there’s more to getting true traction than simply giving startups places to work. Just as a startup needs to do one thing exceedingly well before it tackles other missions, cities should take the same tack and concentrate on one sector of tech to make their own.

I recently was in St. Louis and, while there, I talked to some of its VCs, startups and people who run its incubator and accelerator spaces. Just like anywhere, there exist startups doing all sorts of things in the St. Louis area, but many of the most interesting companies have coalesced around the bioscience space. This isn’t by chance. The city’s tech players have seized on some of the area’s inherent strengths in healthcare and biotech. Washington University, which has one of the top medical schools in the country, is constantly throwing off ideas and graduates who have new ideas in the space. DuPont’s bioscience arm is based here, as is Monsanto, the king of engineered macro-crops. And perhaps most important in all of this, St. Louis was the site of a major set of layoffs by Pfizer in 2010.

St. Louis’ Biogenerator Labs and accelerator. Courtesy: Biogenerator.

The hazard: If the St. Louis community couldn’t find jobs for these people, they would be forced to leave the area, depriving the metro of elite brains that Midwestern cities like St. Louis can sometimes struggle to attract. The opportunity, as Gulve saw it: “These people had been in biotech for years and had great ideas, far better than first-time entrepreneurs coming from outside the industry.”

Gulve asked Pfizer if, before the last day of work, he could come in and present to employees about what working a startup is like and what the landscape was like for funding and founders. Pfizer, which wanted to find new roles for its employees as much as Gulve did, said yes. Gulve came in and gave his presentation to Pfizer employees on-site, and then took five in-person meetings the same day. Biogenerator ended up funding four groups from those meetings, one of which turned into Confluence Life Sciences, which now employs 35 in St. Louis.

At the same time, Gulve was hustling to complete a new building and set of labs for Biogenerator. He wanted it ready to catch some fo the fallout of the Pfizer layoffs. A pilot set of labs opened in the fall of 2010, just a few months after Pfizer made its cuts. The 5,600-square-feet of space was filled within 18 months. Biogenerator used that success to raise a total of $145 million and fund 54 companies that have attracted another $250 million in outside capital. The incubator, part of the Cortex Innovation Community, has also added another 12,400 square feet of lab space.

“If you have layoffs in a city and you don’t have this kind of infrastructure in place, you’re not able to take advantage,” explains David Smoller, a partner at St. Louis’ Cultivation Capital who holds a Ph.D. in molecular biology and has been part of several biotech exits. “A lot of the best intellect in the area is now at these biotech startups.”

The lab space is free for Biogenerator companies—and many of them stay there for years after their initial funding, even after finding traction and hiring a significant number of employees. Lab equipment—stuff like mass spectrometers and automated robotic arms for preparing large numbers of samples—is expensive. Small companies can’t afford to finance a lab all their own—but they also don’t need the lab every hour of the day. This allows several startups to easily share the same lab equipment. It’s a unique infrastructure for rearing biotech companies for which St. Louis has found a niche.

The city may have a chance to repeat the feat with 2,600 global layoffs just announced at Monsanto. It’s unclear where exactly those job cuts will take place around the world, but it’s likely that a few hundred will be in St. Louis. “Hopefully a subset of those people won’t want to retire,” says Sam Fiorello, chief operating officer of the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center. “They know the ag space in and out and we need to be ready to provide them support.”

Danforth has multiple missions, including the pursuit of agricultural solutions to mitigate hunger and disease across the world, but it’s also one the U.S. hubs for new companies focusing on the ag tech space. With labs, office space, mentors and a complete talent network, companies here can stay focused on their product.

Experimental plants being reared at the Danforth Plant Science Center in St. Louis.

Fiorello, who was the chief of staff for Henrik Verfaillie when the latter was Monsanto’s CEO, has been grinding to create a complete program for nurturing ag tech companies and, just as important, a base of employees who can easily be plugged into growing ag ventures. “You can’t just build lab space and expect people to come,” he says. “It’s not a real estate play.”

The biggest pain point for Danforth’s companies has been finding skilled workers for the lab. To that end, Fiorello has worked with St. Louis Community College to create a plant science training program that now boasts a 98% job placement—the remaining 2% go on to get bachelor’s degrees. Danforth, now with two buildings and attracing ag-tech from around the world—including multinational companies from Germany and Israel—now houses 575 people with an addition on its main building that will make room for another 100.

The next project for Fiorello is yet another new building for Danforth that can help him catch Monsanto refugees. One company already using Danforth’s resources, Arvegenix, was founded by three former Monsanto employees who are developing hearty strains of Pennycress, a winter annual plant, as a revenue crop for during what’s normally a dormant period for North American farmers. The plant will provide animal feed as well as oil that can be used in biofuels. Arvigenix has raised $9 million and is now using the core lab at Danforth to develop its seed. Arvegenix has set up shop in St. Louis’ Helix Center biotech incubator, yet another local platform aimed at the space.

St. Louis, like Chicago, has a lot of work left to achieve its goals as a destination and long-term home for tech, but it has made the shrewd choice of identifying sectors where its infrastructure and intellectual capital already had a head start.

Article is courtesy Christoper Steiner at Forbes.com. See the original article here.

Jan 30

Stadia Ventures Announces Move into Cortex Innovation District

Stadia Ventures, the two-year-old sports-focused business development firm and accelerator that helps early stage sports startups connect with investors, brands and teams, today announced it is moving its headquarters into the CIC@4240 building in the Cortex Innovation District next month. Since Stadia started in 2015, its headquarters have been located in T-REX downtown.

“We’re thrilled to move into the Cortex district inside CIC and further engrain Stadia in the growing St. Louis startup ecosystem,” said Art Chou, Stadia Ventures co-founder and Managing Director. “T-REX and CIC play vital roles in the entrepreneurial ecosystem and we look forward to continuing to support both facilities, holding events such as our Spring 2017 Finalist Pitch Day event at T-REX in late February.”

T-REX, which plays hosts to over a dozen entrepreneur support organizations, has been home to almost all of St. Louis’ startup accelerator programs. Prosper Women Entrpreneurs Startup Accelerator, SixThirty and SixThirty Cyber accelerators and the Purina PetCare Innovation Prize are based in T-REX, with the Yield Lab accelerator also having a T-REX office. Capital Innovators, previously headquartered in T-REX, moved to CIC@4240 in 2016 as part of a partnership with Maritz, Inc.

Stadia Ventures focuses on fostering connections between startups and its partners in the $150 billion sports business market including the St. Louis Cardinals, St. Louis Blues, ESPN, CBS Sports, Rawlings, Wilson, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Under Armour, the San Francisco 49ers, the Jacksonville Jaguars, the Philadelphia 76ers and others. Stadia just completed its third cohort.

“The Stadia Accelerator has been a game changer for our business,” said Joe Shuchat, founder and president of Winning Identity, a Stadia Ventures portfolio company and accelerator graduate. “The guest speakers they’ve brought in have been world class industry leaders. The advisory team has put us in a position to take our business to the next level.”

Jan 28

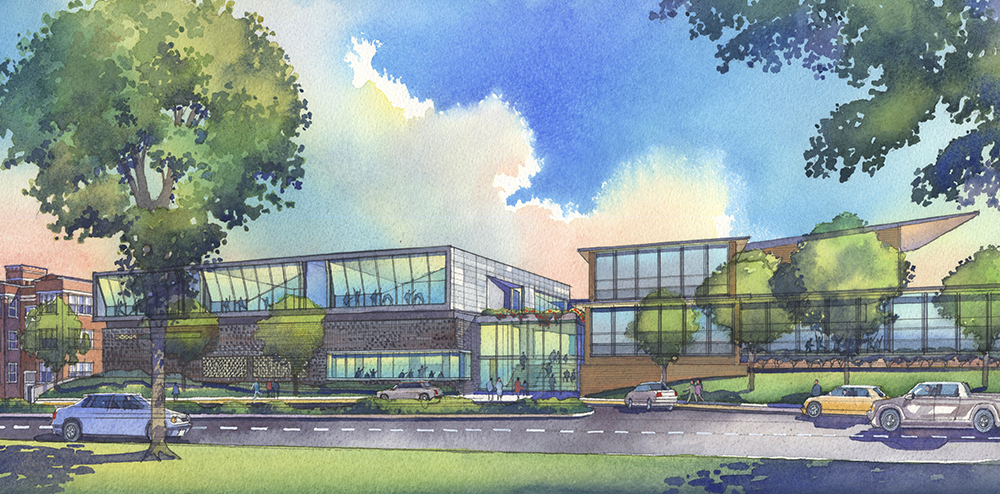

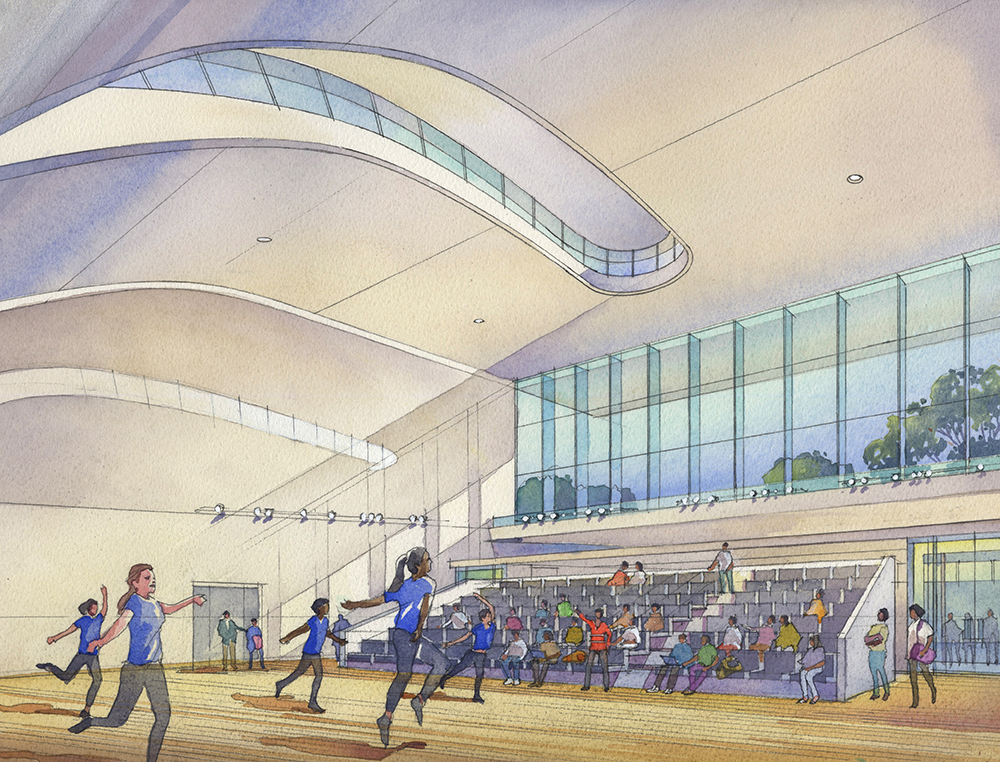

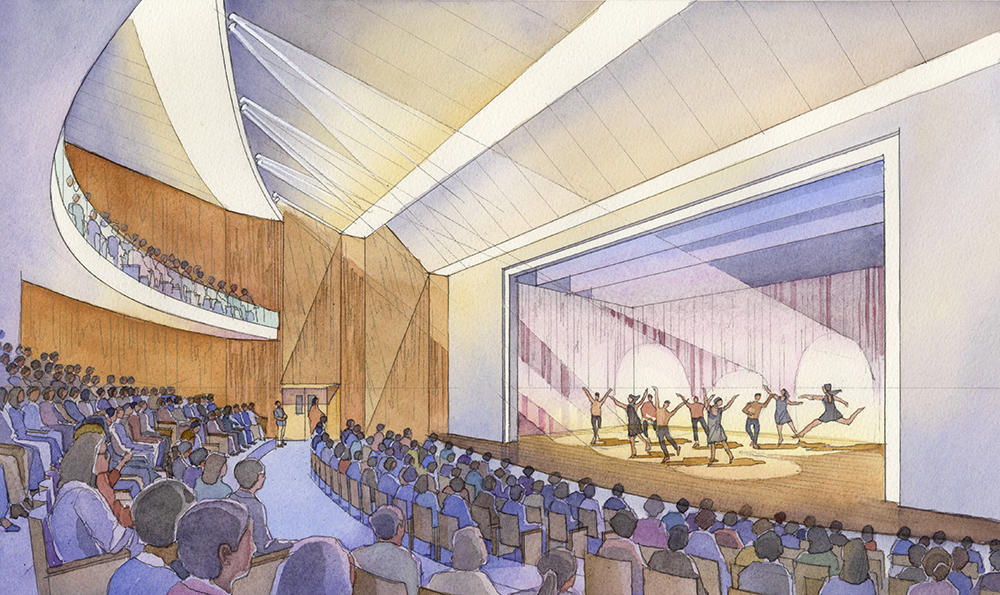

COCA Announces $27M Expansion, Parking Garage in U-City

At its 30th anniversary celebration, the Center of Creative Arts (COCA) in University City announced plans for a $27M renovation and expansion to its home at 524 Trinity Avenue. COCA says more than $25M has been raised toward a $40M campaign which includes $13M toward its endowment and reserves.

Founded in 1986, COCA transformed the B’nai Amoona Synagogue, designed by notable architect Eric Mendelsohn and completed in 1950. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. An 11K sf addition in 2004 created a new entrance and expanded capacity.

The newly announced expansion is planned to begin in 2018 and be completed late the following year. A new 450-seat theater will be built on the existing adjacent surface parking lot and require the removal of the 2004 addition. Other planned amenities include new studio, instructional, and community space.

A 200+ parking space will be constructed in conjunction with Washington University across Washington Avenue, replacing the approximately 80 existing COCA space, and 70 at 560. That garage will serve both buildings. 560 was completed in 1930 as the Shaare Emeth Temple. The building has seen a variety of uses since and was acquired by WUSTL in 2006.

These two buildings and others highlight a challenge noted in the National Register nomination form, “Since this part of University City already has a super abundance of institutional facilities and a shortage of parking spaces, the future of B’nai Amoona is in doubt.”

Indeed, it’s been a challenge to find new uses for some of University City’s institutional buildings. Today, City Hall occupies the “Women’s Magazine Building”, originally built as the headquarters of a publishing company. Next door, the Church of Scientology occupies the 1924 Assumption Greek Orthodox Church.

Today, the former Harvard Delmar School building is vacant, and the magazine press building, long the city’s police headquarters, has been vacated after being deemed unfit for use. The former school building at 721 Kingsland is now utilized by WUSTL’s Sam Fox School.

Mendelsohn, architect of B’nai Amoona Synagogue (COCA), left Germany in 1933 following the rise to power fo the Nazis. He eventually immigrated to the US in 1941.

According to the National Register nomination form, Mendelsohn had a friend in St. Louis for whom he had designed a store in Gleiwitz, Silesia, in 1922. Connections made via his friend led to showing his work, giving lectures, and then the B’nai Amoona commission. The building proved popular and led to commissions in Cleveland, Ohio (1946- 1952); Washington, D.C. (1948); Baltimore, Maryland (1948); Grand Rapids, Michigan (1948-1952); St. Paul, Minnesota (1950-54); and Dallas, Texas (1951).

Design team for the $27M COCA theater and expansion project: Design Architect – Axi:Ome, Associate Design Architect, Architect of Record – Christner Inc., Structural Engineer – OES Inc., Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing Engineer – Buro Happold, Lighting Design – Buro Happold, Civil Engineer – Engineering Design Source, Inc., Theater Consultant – Schuler Shook, Acoustic Consultant – Kirkegaard Associates, Audio Visual Consultant – Kirkegaard Associates, Construction Manager – Wilson TW Joint Venture.

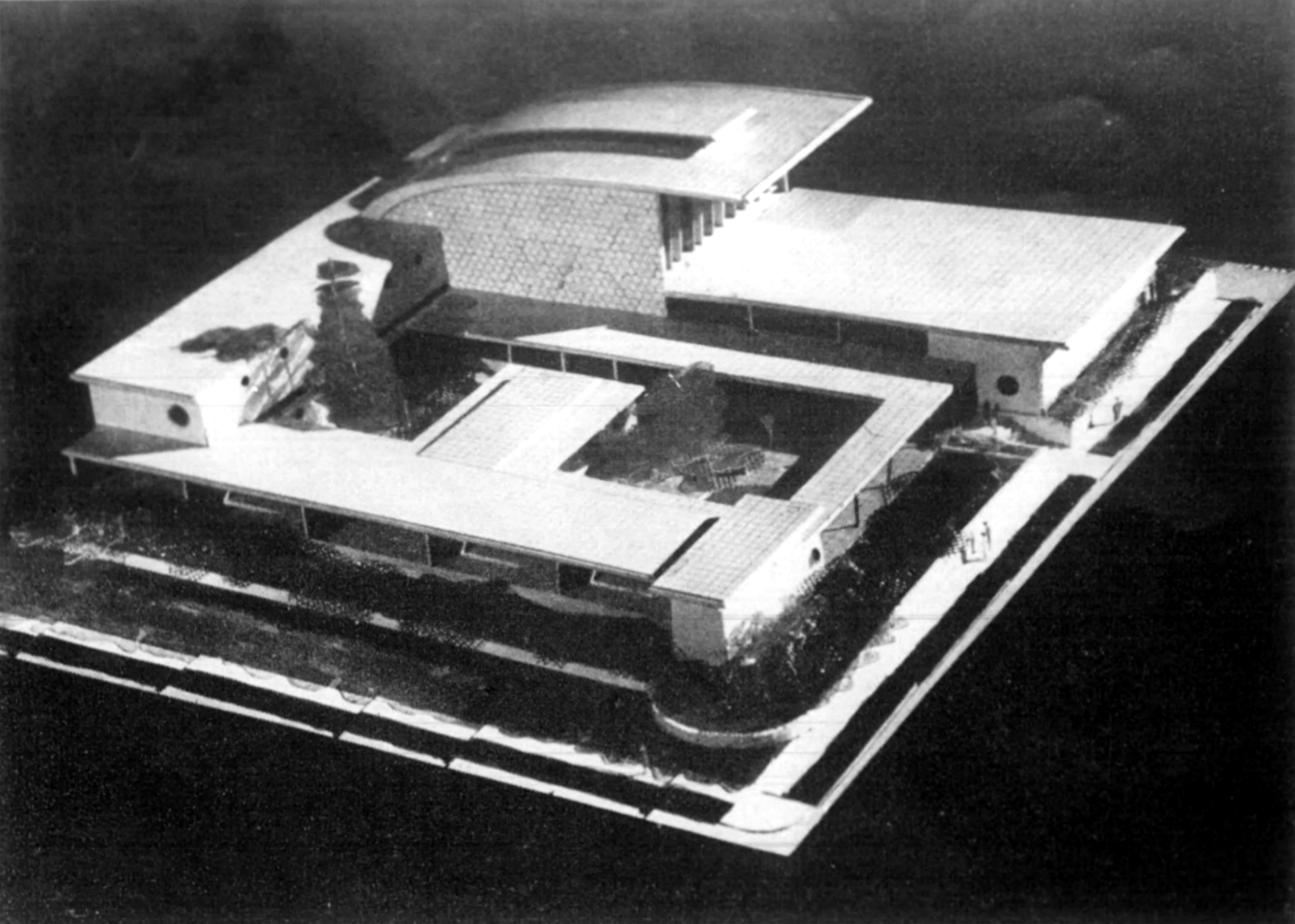

Model and images (1980) from National Register nomination form:

Jan 26

New Residential Infill Nears Completion in Old North St. Louis (1323 Monroe)

A three townhome project at 1323-39 Monroe Street in Old North St. Louis is nearing completion. The 3BD, 2.5BA homes are listed for $155K by Rome West Realty. The three corner lots are three blocks south of the 14th Street project and Crown Candy Kitchen, the urban center of Old North. The neighborhood saw an incredible 27.7% population increase, gaining 416 residents from 2000 to 2010.However, momentum then slowed as the economy faltered, and the big idea, the $4B, 1,500-acre NorthSide Regeneration plan immediately to the neighborhood’s west, never got off the ground.

However, momentum then slowed as the economy faltered, and the big idea, the $4B, 1,500-acre NorthSide Regeneration plan immediately to the neighborhood’s west, never got off the ground. Now two-thirds of the way through this decade, the $2B NGA headquarters project and planned or hoped-for nearby development may return growth to the area. In the meantime, project like this one offer an affordable option and quality infill to an area with high vacancy.

All photographs via Matt Fernandez. Renderings via Rome West Realty.

dafasdfasdfsad

Jan 25

Historic Gratiot School Transformation to 22 Apartments Moving Quickly

The historic Gratiot School at 1615 Hampton Avenue near Manchester Avenue is undergoing a conversion to apartments by Garcia Properties, which purchased the vacant school from the district for a reported $414,700. The building closed in 2013 after having served as home to the St. Louis Public School archives since 1992.

The 27,474 sf school dates from 1882 with additions in 1899 and 1919 and is quite a bit smaller than other former school buildings that have been converted to apartments in recent years. The building will accommodate 22 apartments. Having been used to store archives, the building was in decent condition when sold to Garcia. As of this post, new windows had been installed on the north side of the building (see image below).

Though the school appears rather cohesive architecturally, the center section predates the rest of the structure by several decades. From the National Register of Historic Places:

The east elevation is eleven bays wide, the two-story building has red brick masonry bearing walls laid in common bond resting on a raised, split-faced random ashlar limestone basement. The center section of the building is the original 1882 schoolhouse designed by H. William Kirchner.

The north and south wings of the east elevation are identical in form although they were constructed at two different times. Both wings were probably designed in concept by William B. Ittner c. 1899 although the plans for the southern addition bear Rockwell Milligan’s name. The northern wing was constructed in 1899 under Ittner’s direction. The southern wing was constructed in 1919 under the direction of Ittner’s successor Rockwell Milligan.

[Read Gratiot School National Register of Historic Places nomination]

Gratiot School c. 1882:

Gratiot School and floor plans c. 1935:

Photographs from late 2015 by Andrew Weil for the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form:

Images from Google Streetview and Google Earth:

Images from Paul Sableman via Flickr:

Image by 24th Ward alderman Scott Ogilvie (1/23/2017):